My leadership philosophy - Part 3: Charismatic leadership tactics

Introduction

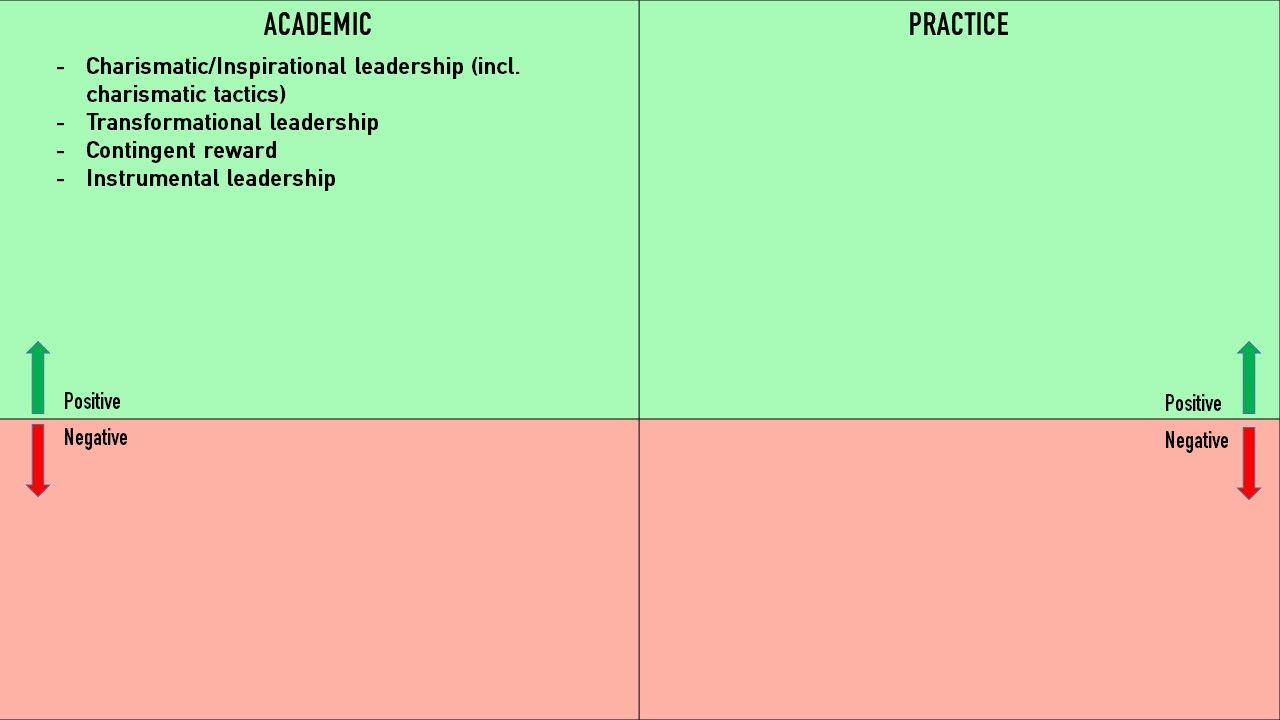

[This article is part of a series in which I'm sharing key lessons I've learned about what drives or derails effective leadership, distilled during my 17 year career assessing and coaching executives. Previous articles included the introduction to the series, a focus on charismatic/inspirational leadership, and a summary of transformational leadership (with mention of two complimentary styles called contingent reward and instrumental leadership).]

In a previous article I described how charisma and inspiration are skills that can contribute to leadership effectiveness.

To help clarify these murky concepts, I distilled charisma and inspiration into 5 key dimensions, based on a review of three major leadership frameworks:

- Being visionary - creating and articulating a compelling vision.

2. Conveying inspiration - encouraging others to succeed, and expressing confidence they can achieve the vision.

3. Invoking integrity/morality/ethics - demonstrating trustworthiness, honesty, and integrity; acting in an admirable way that generates respect; exploring ethical dimensions during decision making.

4. Self-sacrificing - being willing to sacrifice time, energy, effort, or resources as a leader to succeed.

5. Setting high performance standards - setting demanding, difficult goals.

Despite sharing these key dimensions, I wondered if leaders might still need or want further suggestions on how to improve this area of their leadership.

With this in mind, I uncovered additional research that outlines 12 different tactics leaders can use to enhance their expression of charisma, and which I’ll share in this article.

I’ve aggregated these ideas from the work of John Antonakis and his colleagues. They’ve crafted a Harvard Business Review article summarizing these tactics, and I’ve also drawn from his other peer-reviewed academic papers (here, here, and here).

What is charisma?

Charisma is a kind of 'signal' that leaders send to followers, that includes an expression of values (which could be prosocial or antisocial), symbolism (such as the use of metaphors to engage an audience), and emotion (such as the compelling use of body language, gestures, and voice). It’s believed that if potential followers identify with the leader’s values, resonate with the symbols used, and feel excited by their emotional displays, they will support the leader.

Why do I use the word 'signal'?

Signaling is an idea that’s emerged from economics, to explain how parties behave when one possesses more information than another. For example, when a company strives to increase the diversity of its Board members, it’s signaling to the market that it adheres to social values. Or when a company raises its dividend, it’s signaling to the market that its finances are sound and that it’s worth investing in.

In a similar way, leaders strive to signal to potential followers, who may not have full information about the leader's skills, just how credible and capable they are. So I use the term signaling because charisma is one way of conveying that ‘credibility’ message.

Another reason I use the word signaling is that it conveys the notion of communication. And as you’ll see below, the 12 charisma tactics I share involve both verbal and non-verbal forms of communication.

What are the most important charismatic leadership tactics (or signals)?

Based on their research, Antonakis and his colleagues found that the following 12 tactics (9 verbal, 3 non verbal) can contribute to perceptions that a leader is charismatic and effective.

Verbal

Metaphors, similies, analogies

Generally these techniques represent ways a leader creates symbolism by saying one concept is like or similar to another.

This tactic is effective because it simplifies messages, rouses emotions, aids with recall, and makes the leader’s communication more relatable.

One example of this is in a company I’ve worked with, the former CEO sometimes sought to motivate his senior leadership team by asking them to think of themselves as Olympic athletes… “At this company *we are like Olympic athletes* striving to be the best in the world. If we were Olympic athletes, we would accept that we need to push ourselves to the absolute limit in order to reach peak performance. We would accept that there will be pain and stress on the path to reaching our full potential. We would accept that we can’t be comfortable and still reach our peak.” The intent of this symbolic message was to convince other leaders that they should strive to be the best in the world (i.e., win a gold medal), and also to accept the pain, discomfort, and difficulty of the journey.

Stories and anecdotes

This tactic is effective because it immerses the listener, and illustrates a key point.

In another example, also from the former CEO mentioned above, one time he told a brief story saying “when I was younger, I approached my boss at the time and said, ‘I want to do more, I want to do big things.’ He turned to me and said ‘listen to me you little [expletive], responsibility is 80% taken, 20% given.’" The key message was that if you want to do more, step up and show initiative and don’t wait for others in the organization to grant you permission. If you have an idea, put it on paper and present it to an executive.

Moral conviction

This involves showing the moral force underlying the leader’s values and position. Combining a sense of morality with a vision or goal probably creates a ‘moral imperative’ mindset (i.e., ‘I want to do this, and it’s the right thing to do’) which can be powerful in motivating others.

This is effective because it taps into a sense of duty or obligation (i.e., more than just emotion), which can unleash energy and action.

An example of this is when another leader I know explained the rollout of a controversial company-wide Covid vaccine requirement, stating that it was the right thing to do because it protected the safety of the company’s employees and their families.

Make statements that summarize the collective’s sentiments

This involves leaders making statements that capture the general mood, feeling, and values of the collective. It involves leaders speaking for the group, and encapsulating their collective mindset.

This is effective because it gives the listener a chance to confirm that the leader’s sentiments match their own, and if so, they will often further identify with the leader and their goal.

An example of this is Winston Churchill's 1940 speech in which he summarized (and sought to bolster) the resolve of British society, as the German army spread across France:

“We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills…”

Set high expectations for themselves and followers

This involves the leader setting a difficult goal for themselves and others.

An example of this is John F. Kennedy's speech at Rice University in September, 1962, about the United States’ goal to travel to the moon:

"Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, "Because it is there." Well, space is there, and we're going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God's blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked."

(Seven years later, US astronauts landed on the moon!)

Communicate confidence that the goals can be met

This involves the leader expressing confidence that others can achieve the goal.

Examples of this involve leaders saying “I believe we can do this…” or “I believe we can succeed in this objective.”

Contrasts

These are statements that clarify a leader’s position by pitting it against an opposite one.

This tactic is effective because it helps to frame, focus, and clarify a message.

An example of this occurred during Barack Obama’s 2004 speech at the Democratic National Convention:

"…there is not a liberal America and a conservative America; there is the United States of America. There is not a Black America and a White America and Latino America and Asian America; there's the United States of America."

Three-part lists

This involves leaders expressing their ideas in sets of three.

This tactic is effective because three items are easy to remember, suggest a pattern, and create the impression of a complete list

A example of this would be a leader saying “to fight back this threat from our competitor, we need to do three things... 1) spend more time in face to face interaction with our customers, 2) reexamine our strategy for breaking into the US market, and 3) change the labeling on our packaging to better convey our value.”

Rhetorical questions

These are questions leaders ask to create a dramatic effect or to make a point, rather than to get an answer.

This tactic is effective because it demands the audience generate an answer aligned with the leader’s thinking. It also mentally engages the audience in the content of the speech, by posing the question as a kind of puzzle.

An example of this occurred in a speech given by then-presidential candidate Ronald Reagan in October of 1980, in which he criticized President Jimmy Carter in ways that highlighted his vision for enhancing the security and military strength of the United States:

“As a presidential candidate four years ago, [Carter] said: ‘…it is imperative that the world know that we will meet obligations and commitments to our allies and that we will keep our nation strong.’ Did he keep his promise?... Has he kept our nation strong? Are you willing to risk four more years of what we have now? Has the registration and the possible draft of your sons and daughters contributed to your peace of mind? Is the world safer for you and your family?”

Non verbal

Antonakis and his colleagues also highlight the importance of conveying several non-verbal behaviours in order to project charisma.

Body gestures

Leaders can align gestures in a way that reinforces their message, for example with a fist, a waving hand, or a pointed finger.

Facial expressions

Leaders can make eye contact, and convey a range of emotions using facial expressions.

Animated voice

Leaders can also vary their volume and pacing, and strive to convey several kinds of emotions with their voice.

Can charisma be learned?

Yes it can. Antonakis published a paper in which he trained managers in organizations, using the 12 tactics mentioned above.

In one study he trained 34 leaders, and collected 360 survey data about them before and after the training.

In a second study he and his team asked 41 leaders to video themselves giving a speech to their team about facing a difficult situation. Then they trained the managers on the charismatic tactics, and afterwards asked them to repeat the speech. The speeches were coded by independent raters.

Both studies showed substantial increases in ratings of perceived leader competence after participants received training on using these charismatic tactics.

How much is too much?

Charisma is a valuable contributor to perceptions of leadership effectiveness, but is there a limit to it’s benefit?

Another study examined this question and found there might be. A researcher and consultant named Rob Kaiser has generated a considerable body of work suggesting that extremity in various leadership qualities can lead to ineffectiveness. In one study he was involved with in 2018, he examined charisma in this regard.

Sure enough, he and his colleagues found that moderate levels of charisma (measured not with the behaviours cited above, but with a different inventory of charismatic personality), were most effective.

Referring back to Antonakis’ behaviours then, it could be that it’s important for leaders to demonstrate some of these behaviours, but they shouldn’t feel the need to overindex on them or to try to express too many. (Note that Antonakis suggests that we don't yet know which tactics, or combination of tactics might be most effective.)

See below for two examples of speeches given in political contexts in which the speakers overcooked the level of charisma they were trying to project.

Learning methods matter

One important lesson to keep in mind from Antonakis’ work is that while learning charisma is possible, it requires effort and considerable feedback.

Antonakis and his team used a variety of intensive techniques to help leaders learn charisma. These included extensive feedback delivered in a participant-centric way (e.g., by analyzing video of their speeches), focused and explicit development goals, creating awareness of being remeasured after the intervention, showing video case examples (i.e., of famous speeches), and using role playing exercises.

They also found that in the two studies they conducted in which they trained leaders to be more charismatic, that the more intensive of the two training approaches produced the best results.

Developing charisma, like any leadership skill, requires effort and focus.

Conclusion

In this article I’ve outlined 12 specific and evidence-based tactics that leaders can practice to improve the way they project charisma, and lead others.

I hope these tactics provide additional tools leaders can use to further strengthen their approach. I also hope these tactics demystify this concept, and show that with some effort any leader can improve their charisma skills, and in turn how they motivate others.

As always I would welcome your feedback, positive or constructive, on anything you read, and I would love to learn from your perspective.

If you’d like to comment on this article, you can do so below. In order to comment, you’ll need to enter your name and email address, and to click a confirmation email you receive, a process that ensures you’re real and not a robot (you won’t need to create a password). If you prefer you can also email me your comment at tjackson@jacksonleadership.com.

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to receive these newsletter issues direct to your inbox, please click the blue ‘Sign up now’ button below.

Tim Jackson Ph.D. is the President of Jackson Leadership, Inc. and a leadership assessment and coaching expert with 17 years of experience. He has assessed and coached leaders across a variety of sectors including agriculture, chemicals, consumer products, finance, logistics, manufacturing, media, not-for-profit, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and utilities and power generation, including multiple private-equity-owned businesses. He's also worked with leaders across numerous functional areas, including sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, information technology, operations, sustainability, charitable, general management, health and safety, quality control, and across hierarchical levels from individual contributors to CEOs. In addition Tim has worked with leaders across several geographical regions, including Canada, the US, Western Europe, and China. He has published his ideas on leadership in both popular media, and peer-reviewed journals. Tim has a Ph.D. in organizational psychology, and is based in Toronto.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Web: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion