My leadership philosophy: An introduction to the series

What is effective leadership? There are so many answers to this question.

Effective leaders drive change (John Kotter’s ‘Leading Change’), build culture (Edgar Schein’s ‘Organizational culture and leadership’), inspire others (charismatic/inspirational theories), build quality relationships with followers (social exchange theories), adapt to the situation (situational or contingency theories), focus on tasks/results and people (early University of Michigan and Ohio State studies of leadership), show humility (servant leadership theory), set bold goals (Jim Collins’ ‘Good to Great’), demonstrate emotional intelligence (Daniel Goleman’s ‘Primal Leadership’ and other works)… I could go on!

In this post I’m introducing a series of articles in which I plan to summarize some answers to the question of ‘what is effective leadership?’ by reviewing all the key lessons I’ve learned about this phenomenon in my almost 20 years of research and advisory work in the field. The principles I’ll cover represent those that I return to often when trying to understand a leader’s profile of strengths and possible needs, or when formulating a plan on how best to partner with and coach them.

In this introductory article to the series, I’ll start by telling the origin story of how I developed my leadership philosophy. I’ll then explain how the series will unfold, summarizing the broad categories of topics I will cover. Finally, I’ll offer a few humble thoughts on why I think understanding the concepts underlying effective leadership practice is so vital.

The origin story for my leadership philosophy

In 2018 I had the opportunity to meet a CEO at a client organization I had started working with. My contact and the person facilitating the introduction said ‘you should come ready to talk about your leadership philosophy, he may ask you about it.’

This comment made me pause. I had spent the entirety of my professional life (all my post-graduate career, and all of my consulting career) working in leadership development but had never taken the time to write down, in a concise way, what I believed about the subject.

I set about capturing on a single PPT slide everything I thought I knew about leadership, including my beliefs about the drivers and derailers of effectiveness, based on lessons I’d learned in both academic and practice settings.

The meeting turned out to be a hurried though still cordial interaction, in which the CEO shared just one key message: ‘be on your best behaviour when working with my leaders, and don’t screw anything up inside my company.’

In the end, the CEO never asked me about my leadership philosophy. However I held onto that PPT slide and continued to refine it over the next several years. As I built out and added clarity to the model, it grew into a useful reference tool that I used when assessing or coaching clients. I used it to ask ‘am I missing anything?’ when thinking about how to help a leader grow.

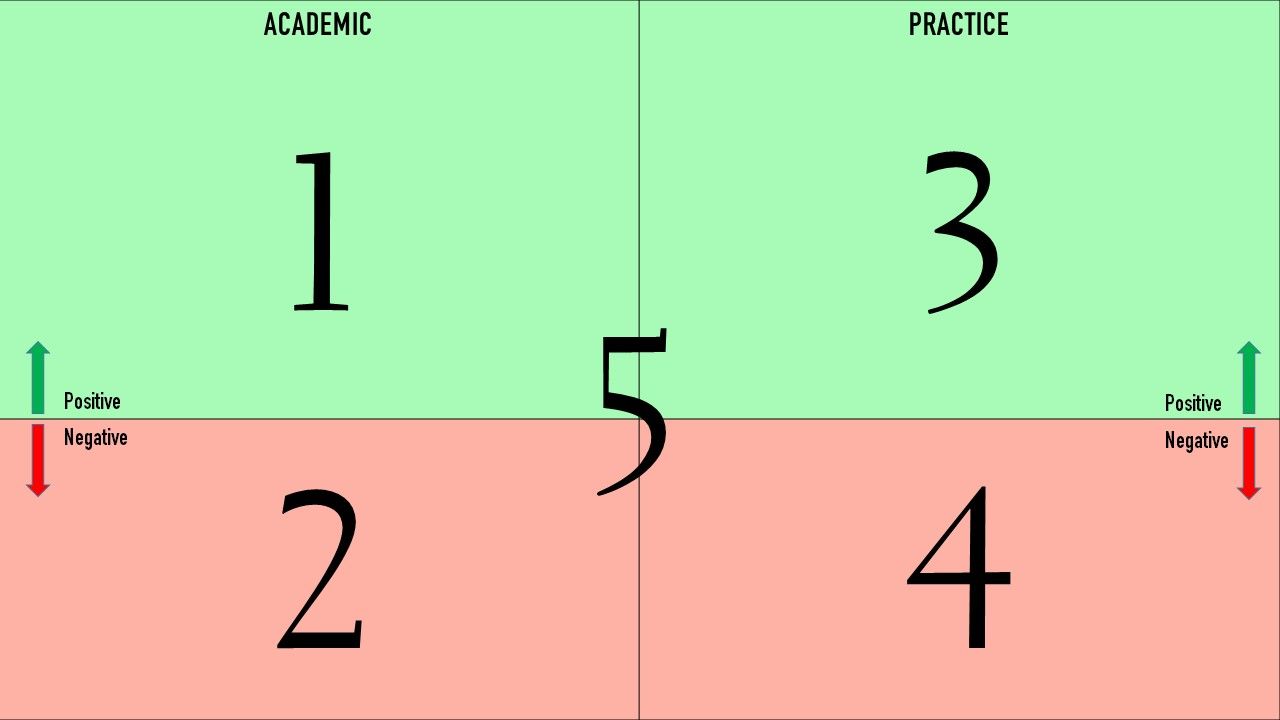

The PPT slide I created was a simple 2 x 2 matrix (see below). On the vertical axis, I divided the rows into concepts that either drive or derail leadership. On the horizontal axis, I divided the columns into concepts that I learned either in academic or practice settings. Finally in the middle of the slide, I placed a few principles that defied categorization in any of the quadrants, but which I believed were valuable insights to keep in mind.

How the series will unfold

For this series, I plan to write about multiple key concepts that reside in each of the four quadrants, as well as in that nebulous middle zone I mentioned.

I also plan to move through topics in the series in a manner mimicking the order of numbers in the matrix below. In other words, in the first part of the series I'll write several articles describing the concepts that I believe contribute to effective leadership, and which I learned in academic settings (i.e., quadrant #1, in the top-left corner). From there, I'll write several articles covering content in quadrant 2, then several articles for quadrant 3, and so on.

As I publish each of the subsequent articles, I’ll also populate the image of the matrix with the concepts highlighted in past and current articles, like a kind of running scoreboard, so readers can keep track of what we’ve covered.

To give you a brief preview, some of concepts I'll write about will include transformational leadership (1), passive-avoidant leadership (2), versatility (3; based on Rob Kaiser's work), rigidity (4), and a principle I'll call 'the downside risk of bad leadership>the upside opportunity' (5; sorry to be cryptic, more on this later).

One disclaimer I'd like to add is that the principles in this model represent concepts that resonate with me based on evidence, logic, or my own direct experience working with leaders and organizations. The list is not meant to be comprehensive, or to cover all possible drivers or derailers of effective leadership. I may also be limited by my own 'positionality' - i.e., I'm a caucasian male, grew up in a middle class family in Canada, and worked the majority of my career in Western countries. So based on these experiences I may be limited in my exposure to some important leadership principles.

Having said all of this, if you read any articles in series and feel that I've missed including an important concept, or haven't described one with as much detail or nuance as I should have, I would welcome your feedback.

Why I think understanding leadership is so important

Before embarking on this journey exploring various principles that might impact the practice of leadership, I’d like to offer some assertions for why I think understanding the concept is so important.

To start very big picture, leadership is an ancient practice of social coordination that transcends every person and culture across the globe. As a tool for structuring our lives, it’s not going anywhere, so it makes sense to understand it and how to do it well.

Leadership has been a subject of interest in societies for millennia. Researchers have found many ancient religious and secular writings from across the globe that reference the importance of leadership, and the qualities that constitute a good leader. In fact, many early descriptions of leaders pre-date the Bible, some reaching into history as far back as 5000-6000 B.C.E. (e.g., Egyptian hierogliphics, ancient Chinese writings by Confucius).

In addition to possessing deep historical roots, leadership is also a universally endorsed social phenomenon. Reviews of anthropological reports from across cultures concluded that leadership was a basic social structure present in all societies studied, regardless of how isolated they were, or whether leadership roles were informal or institutionalized. Another study called The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) project demonstrated that people from cultures across the world possess an understanding of, or mental models describing leadership (these are sometimes called ‘schemas’). Based on the historical lineage of thought and texts relating to leadership, and evidence for its universality, some argue that humans have evolved over thousands of years to adopt leader and follower roles in order to maintain social coordination of groups.

So leadership has been a part of our identities and cultures for thousands of years, and it will continue to help us coordinate collective action in the future. Based on its fundamental role in our lives (both at work and beyond), it makes sense for us to strive to understand it as much as we can, so that we can practice it with the greatest mastery possible.

Understanding key leadership principles is also important because the expertise this knowledge provides is useful in the modern economy, one in which we need motivating leaders to build bonds with a mobile and supply-constrained workforce.

I’d like to illustrate this point with a short discussion of how leadership research evolved in the 20th century. The study of leadership by social scientists started in the 1940’s and 1950’s, by examining the traits (e.g., gender, intelligence, need for power) and behaviours (e.g., task- or people-oriented) associated with effective leadership in the workplace. Later in the 1960’s, researchers expanded their inquiries to consider how leaders could and should change their behaviour to suit the situation. They called these ‘contingency’ models of leadership, and today this approach is known as ‘situational leadership.’

After this profitable start, however, leadership research entered a crisis of faith in the 1970’s. At the time several scholars criticized research on the subject as uninformative, asserted that the impact of leadership on organizations was negligible, and even recommended abandoning the formal study of leadership (!).

Then, in walked the 1980’s.

This decade was characterized by downsizing and changes in organizational structures, in response to heightened market competitive forces. As a result, companies needed leaders to both guide organizational changes, and to safeguard and even build employee morale during this time of uncertainty. As a result interest increased in explaining how leaders might inspire, empower, and evoke emotional connection with followers. In the absence of assurances of long-term employment, organizations needed leaders who could motivate followers to self-sacrifice, commit to difficult objectives, and achieve more than expected.

Amidst this changing landscape, starting in the mid-1980s research on leadership exploded, in particular on forms that could inspire and motivate the workforce. (I’ll mention some of this work in the next article on charismatic/inspirational leadership.)

My point is that the contextual and business forces that nurtured an interest in the dynamics of leadership in the 1980’s are still present today. Long-term tenure with a single employer remains rare. Since employees are mobile, in particular in the labour-constrained post-Covid period, this increases demands on leaders to motivate their workforces and to foster attachment to their companies.

Since the business dynamics that elevated interest in, and the importance of leadership are still present, this suggests that learning about and practicing effective leadership is as relevant today as ever.

Another reason I believe understanding leadership is so important, is that leaders still exert significant influence over many aspects of organizations.

Despite the protestations of those academic critics of leadership back in the 1970s, and even in light of trends like fostering employee empowerment, and migrating to virtual/hybrid working which reduces opportunities for direct supervision, leaders still exert enormous influence on organizations.

For example, they hold tremendous power to shape culture and values. They exert influence over budget decisions and the distribution of resources. They help create and communicate strategy. They make final ‘tie-breaking’ decisions on intractable issues (in particular during crises). They facilitate execution by clarifying the organization’s priorities (e.g., ‘the CEO says she cares about this, so we have to do it!’). They contribute to critical hiring decisions for key roles.

Sometimes senior leaders are so influential, that an organization takes on their entire persona. I’ve encountered several cases over the years where executives said to me ‘this company is a manifestation of the CEO’s personality.’ If this is the case, it seems critical to support these individuals in understanding what behaviours lead to productive and psychologically motivating workplaces.

Also if you’ve also ever lived through a succession process, or a large corporate merger/integration, both of which create enormous ambiguity about who the leader is and who holds decision making authority, you may possess extra appreciation for the clout of leaders. In those situations, workflow often slows considerably because team members don’t know what’s a priority, and don’t know who to seek help from in order to make a decision.

So despite several decentralizing forces at play in many work environments (e.g., emphases on empowerment, virtual/hybrid work), it’s clear that leaders continue to shape organizations and the work experiences of employees in meaningful ways. Because of their cascading influence on others, it seems critical to help leaders expand their understand of how to wield their power in benevolent, constructive, and effective ways.

Conclusion

I hope you’ll join me on this journey through some of the concepts that I’ve used to enrich my understanding of leadership in the last 20 years.

Next week I’ll start the series with an article about charismatic/inspirational leadership (one of my favourite topics).

As always I would welcome your feedback, positive or constructive, on anything you read, and I would love to learn from your unique perspective. If you've signed up to receive the newsletter you can leave a comment on the article webpage, otherwise you can email me directly at tjackson@jacksonleadership.com.

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to receive these newsletter issues direct to your email, please click the blue ‘Sign up now’ button below.

Tim Jackson Ph.D. is the President of Jackson Leadership, Inc. and a leadership assessment and coaching expert with 17 years of experience. He has assessed and coached leaders across a variety of sectors including agriculture, chemicals, consumer products, finance, logistics, manufacturing, media, not-for-profit, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and utilities and power generation, including multiple private-equity-owned businesses. He's also worked with leaders across numerous functional areas, including sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, information technology, operations, sustainability, charitable, general management, health and safety, and quality control, and across hierarchical levels from individual contributors to CEOs. In addition Tim has worked with leaders across several geographical regions, including Canada, the US, Western Europe, and China. He has published his ideas on leadership in both popular media, and peer-reviewed journals. Tim has a Ph.D. in organizational psychology, and is based in Toronto.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Web: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion